Fluxus was a group of avant-garde artists, poets, designers and architects. Most prolific in the 1960s and 1970s, Fluxus art practices emphasized experimentalism, chance, and the blurring of art and life. Fluxus was inspired by previous artists and movements including Dadism, Brutalism, Haiku, Marcel Duchamp and the experimental music and teaching of John Cage. Individuals associated with Fluxus included George Maciunas, Dick Higgins, Alison Knowles, George Brecht, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Joseph Beuys, Robert Watts, La Monte Yong and Alan Kaprow. Fluxus was, and is, a radical departure from traditional conceptions of art, with key members understanding their practice to be social and participatory rather than aesthetic. As Ken Friedman (1998) reflected on the Fluxus relationship to the art world, “art was so heavily influenced by rigidities of conception, form and style that the irreverent Fluxus attitude stood out like a loud fart in a small elevator” (p. 249).

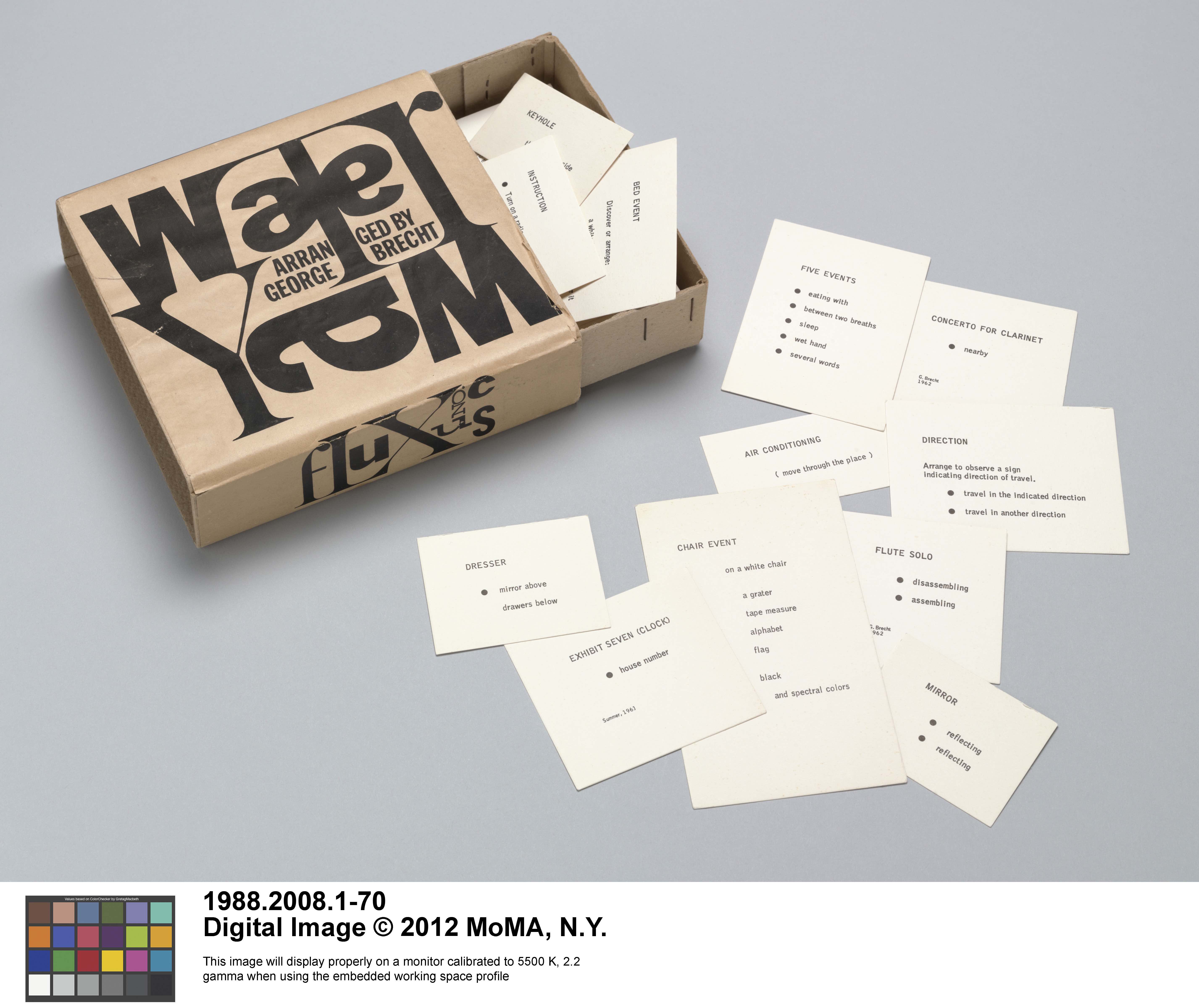

One of the most explicitly articulated visions of the Fluxus philosophy can be found in the Fluxus Manifesto written by George Maciunas in 1962. Maciunas’ explained that the purpose of Fluxus was to “purge the world of bourgeois sickness…Purge the world of dead art, imitation, artificial art, abstract art.” This was followed by the Fluxus desire to promote “living art, anti-art…to be grasped by all peoples, not only critics, dilettantes and professionals.” Significant Fluxus projects included George Brecht’s Water Yam, a cardboard box housing an assortment of printed cards in various sizes that contain abbreviated, haiku-like prompts called ‘event scores.’ These open-ended instructions invited participants to enact everyday actions or contemplate impossible scenarios. This eventually morphed into what became known as Fluxkits, which often included a wide range of objects and provocations often contained within a suitcase or box.

Fluxkits and Flux editions were often presented to audiences during Fluxus performances. What was consistent across the Fluxkits and Fluxus performances was that each had a sense of immediacy and both were created with rationally defined parameters in mind. This is not to suggest that Fluxkits or Fluxus events were rigidly choreographed, but rather that enabling constraints were put in place to guide indeterminacy and chance. For example, a famous 1962 piano performance created by Philip Corner and produced by Maciunas called Piano Activities included ‘event scores’ for nine possible roles for “many pianists.” Possible roles included “playing the piano in an orthodox manner, dropping objects on the strings, acting on the strings with objects such as hammers or drum sticks, and “acting in any way on the underside of the piano.” Overall, the Fluxus approach gave rise to new conceptions of art and education and is related to a notions of intermedia and interdisciplinarity in which knowledge flows across disciplinary boundaries.